There are important events that happened in November at Sotterley over the centuries. Some were tragic, some celebratory. They are all connected.

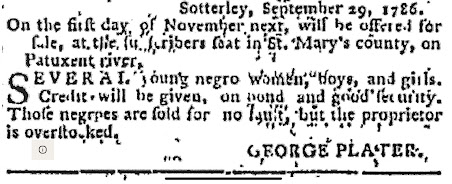

This advertisement above, dated September 29, 1786 from George Plater III, announces an event happening at Sotterley on November 1, 1786.

"On the first day of November next, will be offered for sale, at the subscribers seat in St. Mary's County, on Patuxent river, several young negro women, boys, and girls. Credit will be given, on bond and good security. Those negroes are sold for no fault, but the proprietor is overstocked."

In the letter below, dated November 7, 1861, one of Walter and Emeline Briscoe's sons, Chapman, is requesting an alternate assignment. Chapman had been very ill as a child, and life in the field had proved too much. Three Briscoe sons joined the 1st Maryland, a Confederate unit in Virginia. Chapman remained in Richmond, VA after the war and married there.

"Richmond Nov 1. 1861

Dear Sir

Ill health has compelled me to give up my position in the 1st Maryland in which I have been since the war commenced, and not being able to sustain myself here without employment, I herewith make application for a clerkship in your detachment. References as to qualifications, ie will be furnished if required.

Hoping you will be able to favor me

I am very respectfully yours

Chapman B. Briscoe"

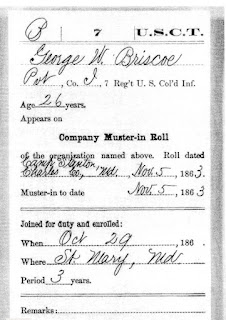

A wealth of information in a small package, this Muster Roll document, (above) dated November 5, 1863, is for George W. Briscoe, who is also on the Slave Statistics of St. Mary's County under Walter Briscoe of Sotterley. Here George is on this roster on Oct 29, and on other documents is listed September 1863 the time he left Sotterley. He is serving at Camp Stanton in Charles County. Camp Stanton was a training camp for USCT solders, with horrid conditions, many died there. George would survive the camp. In later widow pension documents we find that George had received the name Briscoe from the Army, his name was actually George Washington Barns, as the explanation was "there were too many people named Barns." George served in the USCT 7th Regiment, Company I.

November 1, 1864 is celebrated as Maryland Emancipation Day. Hard won by a very small voting margin, the document stipulating the end of slavery in Maryland took effect on November 1, 1864. Still trying to receive reparations for lost property, former slave holders in Maryland drew up lists of everyone they said they "owned" on November 1, 1864, to include Walter Briscoe and his brother-in-law next door, Chapman Billingsley. They never got reparations, but the document left behind (below) is priceless today. Thanks to the hard work of Agnes Kane Callum, it was transcribed and is easily accessible online at the Maryland State Archives.

On November 12, 2012, Sotterley and the Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project had a ceremony commemorating those who perished and those that survived the Middle Passage from West Africa to Sotterley. The weather was gorgeous and the ceremony and fellowship was mindful, mournful, and inspiring. Ann Chinn is seated below.

Audience 2012

On November 1, 2014, Sotterley placed its Middle Passage Marker. Same emotion filled event, even if it rained.

Audience at marker, 2014.

Many Novembers have passed during Sotterley's history, and with every passing year, new stories of Sotterley's people are discovered and told.

J. Pirtle